It's Greek to Me: "Noble Marbles" Lecture and Exhibit at the Carlos Museum

Back I went this week to Emory’s Michael C. Carlos Museum to hear Curator of Greek and Roman Art Jasper Gaunt hold forth on the history of travel to Greece.

Gaunt, a British-accented, tweed-jacketed classics professor prototype whose necktie featured tiny amphorae, led about 40 of us art, history, and travel enthusiasts on a tour of In Search of Noble Marbles: Earliest Travelers to Greece. The exhibit runs through April 9th, 2017.

Gaunt explained that after the conquest of Constantinople by Sultan Mehmed II in 1453, hostile, intolerant government policy blocked access to Greece for hundreds of years. Only a privileged few outsiders ever visited.

One of the many antique books on display (photo: Emory University)

One of the many antique books on display (photo: Emory University)

The books, maps, and early photographs on display document those rare visits. Intrepid travelers recorded their impressions, described in detail the man-made and natural scenery, and drew illustrations of ancient sites and monuments that, at the time, were impossibly remote.

These travelogues have served as invaluable guides in the creation of gorgeous neoclassical art and architecture around the world, as blueprints for reconstructing and repairing damaged or missing artifacts, and to help in identifying plundered antiquities.

On exhibit were not only several of these eye-witness testimonies, but also a few amusingly clueless depictions of the ancient sites as imagined by those who’d never been.

Gaunt told us that no 1596 audience member watching A Midsummer Night’s Dream had the vaguest idea what Athens really looked like. Shakespeare could just as well have set his play on the moon. And in the exhibit, a 1493 German book lay open to a drawing showing an artist’s rendering of Athens as a walled town of dark, low stone buildings -- a scene so Teutonic it easily could have included a pretzel shop and beer hall.

OK, so, that’s interesting enough. But take a look at this 1682 drawing:

Temple of Minerva (the Roman name for Athena) or, The Parthenon,

Temple of Minerva (the Roman name for Athena) or, The Parthenon,

drawn by Vincenzo Coronelli in 1682.

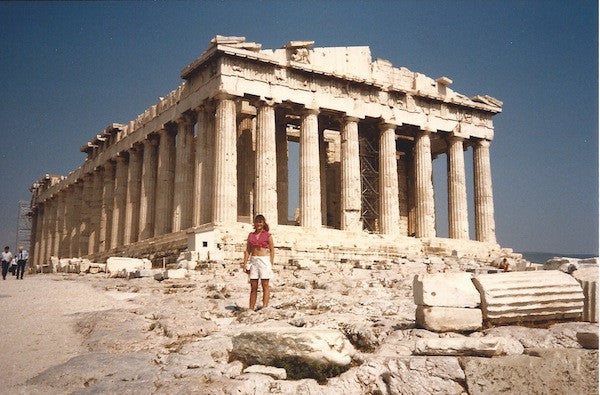

When my friend Karima and I visited the Acropolis in 1986, we assumed that centuries of rain, wind, earthquakes, looting, and pollution had rendered the magnificent Parthenon -- named for the goddess Athena Parthenos, literally Athena the Virgin -- a ruin. There was no docent or informational sign to correct our misapprehension.

Built by Pericles in the mid 5th century BCE on the site of an earlier temple, the Temple of Athena the Virgin became the Church of Mary the Virgin (oh, those irksome patriarchs and their obsession with female virginity) in the 590s. It remained a church for nearly 1,000 years, until it became a mosque under Turkish rule. Each iteration involved decorative and structural changes to suit its current purpose. The Turks added a minaret, for example.

When English clergyman and travel writer George Wheler visited Greece in 1676, he saw the near-complete structure shown in the above illustration, from his book A Journey into Greece, published in 1682. The Parthenon had survived mostly intact for more than 2,000 years, and then, relatively recently, something terrible happened.

Under siege by Venetian Holy League forces, the Turks fortified the acropolis and stashed their gun powder, plus 300 women and children, in the Parthenon for safe-keeping. They figured no Christian army would attack a former church of such historical significance. They were wrong. More than 2,000 shells hit the Acropolis. Two hit the explosives, blowing the ancient Parthenon and everyone inside to bits. Not rain, not earthquakes. War and religion. Same as ever.

Venetian artist's take on the destruction of the Parthenon

Venetian artist's take on the destruction of the Parthenon

by mortar shelling in 1687.

In reality there was no quaint, Phillip Johnson-esque* architectural detail created by the shelling. Sculptures not destroyed in the blast were eventually carted off to distant lands. The rubble was used to build an assortment of new structures in and around the ruined temple. The 1839 photo below shows what was actually left. This was before poorly conceived reconstruction efforts in the late 19th and early 20th centuries caused even more damage:

Earliest known photo of the Parthenon, taken in 1839.

Earliest known photo of the Parthenon, taken in 1839.

When I was there, comprehensive restoration efforts had already begun. Gaunt mentioned the debate within academia about what and how much of the original structure and ornamentation should be restored. Will it still be the Parthenon if a considerable portion is reproduced with modern materials, using modern techniques and technology?

Somehow, I’d managed to visit the place, earn a bachelor’s degree in Philosophy, and live another 30 years under the naive delusion that natural forces and a few overzealous souvenir seekers had, over time, toppled the enormous temple.

Sure, I’d taken Latin (oh boy, did I ever), not Greek. And no, my studies didn’t focus on the Greek Philosophers. But still, isn’t this history I should have known? Some lousy liberal arts major I am. So embarrassing. This, like so many other things, makes me wonder what else I know incompletely, incorrectly, or not at all.

* Broken bonnets: