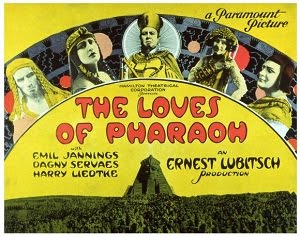

Silent Movie - "The Loves of Pharaoh"

Recently, my vintage-loving friend Kat and I joined an eclectic and enthusiastic crowd at Emory University's beautiful Carlos Museum for a free presentation of the restored 1922 Ernst Lubitsch silent film The Loves of Pharaoh.

David Pratt, PhD, of Emory's Department of Film and Media, began the program by placing the film into cinematic, political, cultural, and historical context.

He told us that after WWI, control of the film industry shifted from France to the United States. The Loves of Pharaoh, which surpassed any European film previously made in both scale and cost, was U.S. funded and filmed with American equipment. German-American director Lubitsch shot the entire film (original title Das Weib des Pharao or The Pharaoh's Wife) in Berlin. Widespread post-war unemployment meant plenty of extras available for the grand crowd and battle scenes -- at the time the most ambitious ever filmed.

The plot line resembles an opera -- soap or otherwise. Think big, implausible melodrama with slave girl stolen and Pharaoh smitten. To get a feel for the film, watch this high-quality 1-minute montage of scenes.

I'm not a film critic, and there are plenty of professional write-ups on the merits and flaws of the film itself, so I'll leave that to the experts. I was there for the drama, the music, the history, and the costumes.

Pratt told us that a second wave of Egyptomania had taken hold in the U.S. and Europe long before the film was made, and would reach a fever pitch with the discovery of King Tut's tomb in November 1922, just a few months after its release.

Egypt-inspired motifs can be found on every imaginable item of the period. All manner of clothing, jewelry, and household and decorative wares were woven, engraved and emblazoned with hieroglyphs, scarabs and cartouches:

Beaded purse, c. early 1900s, Indianapolis Museum of Art

Beaded purse, c. early 1900s, Indianapolis Museum of Art

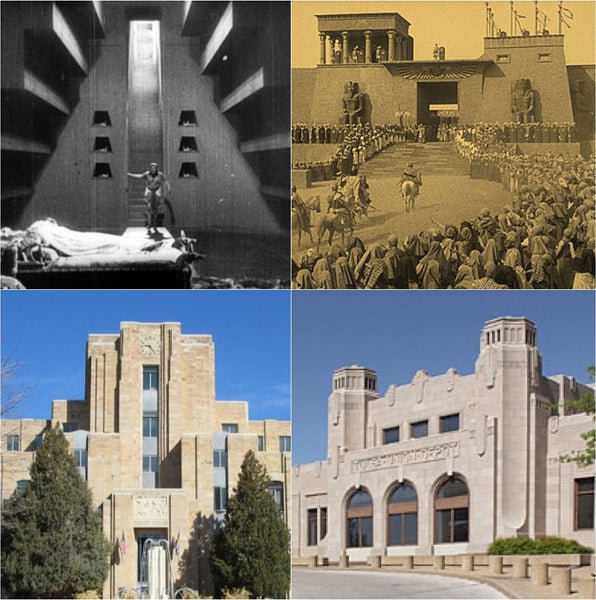

I was familiar with the stylistic fad as it related to fashion, but Pratt showed us the link went further. The familiar symmetrical geometry of Egyptian-inspired motifs clearly influenced the burgeoning Art Deco movement. Side-by-side images of movie sets (top) and art deco buildings (bottom) illustrate his point:

L: Boulder County (Colorado) Courthouse c. 1933; R: Tulsa (Oklahoma) Union Depot c. 1930

L: Boulder County (Colorado) Courthouse c. 1933; R: Tulsa (Oklahoma) Union Depot c. 1930As award-winning musician Donald Sosin struck his first notes on the grand piano, we were mesmerized. I'd been to other events of this sort. Back in the 90s, a bar in the tattoos-and-noserings part of town presented a series of silent films, each accompanied, to varying degrees of success, by local bands. This presentation was on a different level. For one thing, everyone appeared to be sober.

For decades, The Loves of Pharaoh was assumed lost. Then, in 1970, a badly damaged print was found in Russia. By 2011, Alpha-Omega GmbH had cobbled together that tattered copy and bits of another from Italy, eventually producing the beautifully clear and crisp, hand-tinted, nearly complete restoration we watched. Smooth as any modern feature, this wasn't the herky-jerky experience you imagine when you think "silent movie." Stills and explanatory titles patch the few segments of still-missing footage.

Lubitsch was known for comedies. This film wasn't among them. But every so often, we burst out laughing. Sometimes it was less-than-flattering wardrobe, sometimes politically incorrect titles. But most often it was over-the-top, melodramatic acting that set us off. I kept thinking of Gloria Swanson's famous line from Sunset Boulevard: "We didn't need dialogue; we had faces!"

I wondered how different things were when The Loves of Pharaoh was thoroughly modern. Had any of those now-laughable aspects of the film struck the 1922 audiences as funny? What scenarios from our current dramatic cinema will send future audiences into fits of giggles, while wondering what our long-ago reaction had been?

Everyone seemed to enjoy the show and the film ended to hearty applause.

Afterward, Kat and I spoke briefly with Mr. Sosin. She described his piano accompaniment as transporting, and I agreed, although I'm unclear whether Sosin played his own composition or a piano adaptation of the original full-orchestra score. Either way, it was a highlight.

Kat told me her thoughts kept returning to what it must have been like to be an audience member in 1922, imagining herself there in the theater, wearing the clothes, seeing the spectacle for the first time.

Surely the enormous crowd scenes, towering sets, and dramatic lighting would have seemed remarkable. No one had yet seen such grand-scale production.

As for me, I couldn't stop wondering whether the ladies of 1922 found the romantic lead as unappealing as I did. Call me unkind, but manboobs, pasty thighs, and an Edith Head haircut just don't inspire pining. Here, our heroine, the slave girl Theonis (Dagny Servaes) is wooed and won by icky heart-throb Ramphis (Harry Liedke), son of the Pharoah's master builder. Note their pre-code all-legs-on-the-bed pose:

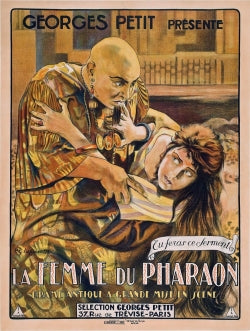

According to Pratt, The Loves of Pharaoh was altered at the whim of local authorities to suit regional tastes and mores. Thus, audiences in different countries saw very different films. In Russia, for example, the war scenes were emphasized and love scenes cut. In Italy, naturally, the opposite occurred. Even the ending -- happy, sad, or a little of both -- depended on your location (no spoilers here, you'll have to find out for yourself what happens in the restored version).

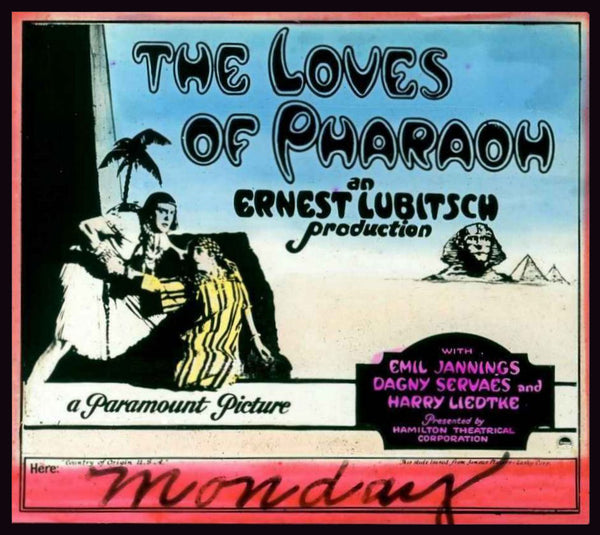

The film's world premiere at Manhattan's Criterion theater was a huge success. The Times ran a rave review. But small-town America was not impressed, and rather than the typical week-long run, some theaters offered only a single showing. This one sadly relegated to a Monday:

As with the film itself, the promotional materials reflected a variety of national tastes. Compare the U.S. poster, at the top of this post, with this one, from France:

One thing I noticed with interest was that dramatically beautiful, but far from skeletal, Dagney Servaes had little in common with either waif-like starlets or voluptuous screen sirens of later years. Put bluntly, our lovely leading lady was a bit dumpy. Did tastes soon change? Were expectations more realistic? I have no explanation.

Other silent-film stars were also strikingly attractive, with unique and expressive faces. But bodily perfection did not appear to be a criterion for a romantic lead at the time. So what changed? And why? And when?

Comments

Thoughtful, perceptive review. You brought a lot to this event, and your comments and questions show your fine mind. Thank you for sharing.

Liza, this was a great blog! I enjoyed seeing all of the jewels in the photos and, like you, found the appeal of the “Heart Throb” of the film definitely leaving something to be desired even for those times. I have been watching some of the old silent films here of late that are being shown on TCM and, to my surprise, am really enjoying some of them…..even though some are a bit over dramatic by today’s standards and come off a bit amusing! I am and always have been totally attracted to Egyptian motifs and this was a nice treat. You and your friend must have had a lovely time at this event and hope you wore something Egyptian!