Lecture - "On Cameos: From Antiquity to Present"

A few nights ago I attended another lecture at Emory University's Carlos Museum.

No matter how esoteric the topic, these free and open-to-the-public presentations always draw an enthusiastic crowd.

Kat and I saw a restored silent movie with live piano accompaniment. Prior to that I'd taken my 8-year-old to hear the world's foremost authority on all things buried by Mount Vesuvius talk about Herculaneum. Speakers come from around the world and their areas of expertise are diverse.

This time I went solo to learn about cameos (carved, not movie). I'm not a jewelry buff, but it sounded interesting. And I'd promised far-flung friends that I'd take notes and share what I learned.

The presenter, Gertrud Platz-Horster of Berlin, is a reknowned scholar of antiquities, with a particular interest in ancient gems and jewelry. She's written several texts on the subject.

First, she explained the difference between a cameo ("jewel") which is carved in relief (raised from the surface) and an intaglio ("seal") which is engraved (cut into the surface).

Cameos have traditionally been made in Egypt, Greece (Naxos), and Italy (Naples), and are carved in stone. Often and most spectacularly, in gemstones with multi-colored strata, like this layered agate:

The rare, highly coveted types of stone used in cameo making are found only in a few places worldwide, including spots in Europe, northern Africa, and India, and are so prized that the world's top-notch deposit, in Thrace (modern-day Bulgaria), was a highly guarded secret for centuries.

If you're a skilled artisan, you can look at a cross-section of your piece of fancy rock and plan your design so the resulting image is both highlighted and backed by contrasting colors, as in the five-layer "Great Cameo of France" from 23CE, the world's largest (it's a foot wide):

I was surprised to learn that since antiquity, cameo makers have used a combination of dye (most often honey) and heat to accentuate the naturally occurring differences in color.

This process of carving and dyeing stone to create detailed, multi-layer artworks has been around since at least 2000BCE.

Platz-Horster showed us this remarkably detailed, tiny Medusa head from ancient Rome. As the image below it shows, it's set into a ring (as were most cameos until fairly recently), and you can see how high above the surface the carved images could rise.

(The above slide also shows quite clearly how rings changed shape over the years.)

Cameos are created using tools similar to a dentist's drill, with the same scary array of detachable heads for fine and gross detail. The only difference between hand-carved cameos made today and those made in antiquity is that modern machinery is electrified, while the ancients used a pedal-powered system similar to a treadle sewing machine.

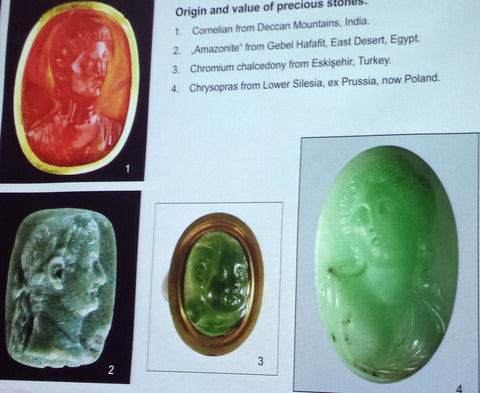

Not all cameos are multicolor. Here are some of the most prized monochromatic gemstones:

The most fascinating portion of the talk was a bit of "CSI: Cameo." Just as X-rays of paintings sometimes show an older work hiding beneath, very old cameos can show evidence of being recarved to suit the "modern" tastes of a wealthy patron or powerful ruler.

Platz-Horster showed us close-ups revealing a reworked profile and tell-tale tool marks where a 2nd century BCE bust of Caesar had become a Renaissance aristocrat. With the requisite background information, and a keen eye, the redo was obvious (sorry, missed the photo op).

She also related a serendipitous twist on "your vintage is not as vintage as you think." All evidence suggested that the pegasus cameo shown below at top right was 18th century. Then, someone noticed that the woman in the 16th century painting at left, housed in another department at the same museum, wore an identical piece on her hat. The cameo was much older than previously thought! Neato.

While describing the preferred subject matter of cameos, how it changed over the centuries, and where artists took their inspiration, Platz-Horster showed us the image below. It's my favorite of the presentation. The turn-of-the-19th-century souvenir cameo is quite clearly based on the 1st century fresco in Herculaneum (and my Emory lecture series comes full circle).

Most modern (as opposed to ancient) cameos were purchased as souvenirs by young upper-class men making The Grand Tour between the late 1600s and early 1800s. Some of the same workshops they'd have visited during that golden age of cameo carving are still active in Naples and Florence today.

Following the talk, Platz-Horster came out from behind the podium for a brief Q&A session.

I had a question. Truth is, I was a bit confused. What about shells? Weren't even really old cameos sometimes carved on shell? What are all these pink and white cameos we're so familiar with? I never got a chance to ask Platz-Horster, so I consulted a few jewelry and antiquities web sites, as well as good ol' Wikipedia.

And yes, of course, as far back as the Renaissance, cameos have been carved on sea shells. But because shell is much softer and easier to carve than any gemstone, cameos made from sea shells have never been as valuable or prized as their hardstone counterparts.

And unless I missed it, which is entirely possible, Platz-Horster did not mention layered-glass cameos, either. Those have been around since the 1st century CE. She focused solely on the carved gemstone variety.

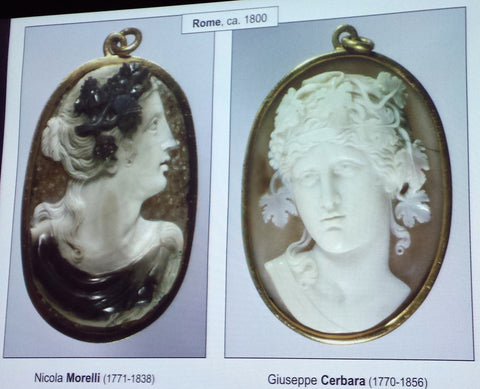

Here are particularly lovely turn-of-the-19th-century examples. The grape-leaf motif is a nod to Bacchus, the god of wine, who happened to be "trending" at the time. These pieces are by two well-known artists of the day.

Comments

Most interesting subject. I had never realized honey had been used to dye the cameos.

Thank you for sharing with us.

Thanks ever so much Liza for posting this so we may all gain from this lecture – I would have loved to have been there.

I am surprised a scholar from Berlin did not mention the major agate carving industry of the Idar-Oberstein region of Germany.

Originally spurred by local sources of the layered stone required for cameo work, it was kept alive, after these sources were fairly played out in the the early 19th century, by the discovery in South America by German immigrants of vast deposits. Unlike the native stone, the South American material was an uninspiring off-white/grey. However, the different layers are of different degrees of porosity & take dye differently as a result. Many modern (19th century & later) ‘hardstone’ cameos we see available for sale these days, the ones featuring a lavishly dressed noblewoman of an earlier time, are of this type.

The pink & white shell cameos are done in conch shell; the brown & white ones use any of several varieties of helmet shell.

Judith, I believe she did mention Idar-Oberstein. There was so much history and technical detail provided (and in heavily accented, if completely fluent, English), it was all I could do to keep up. Thanks for this additional information, and for taking the time to comment! – Liza